©Ananta/Bal

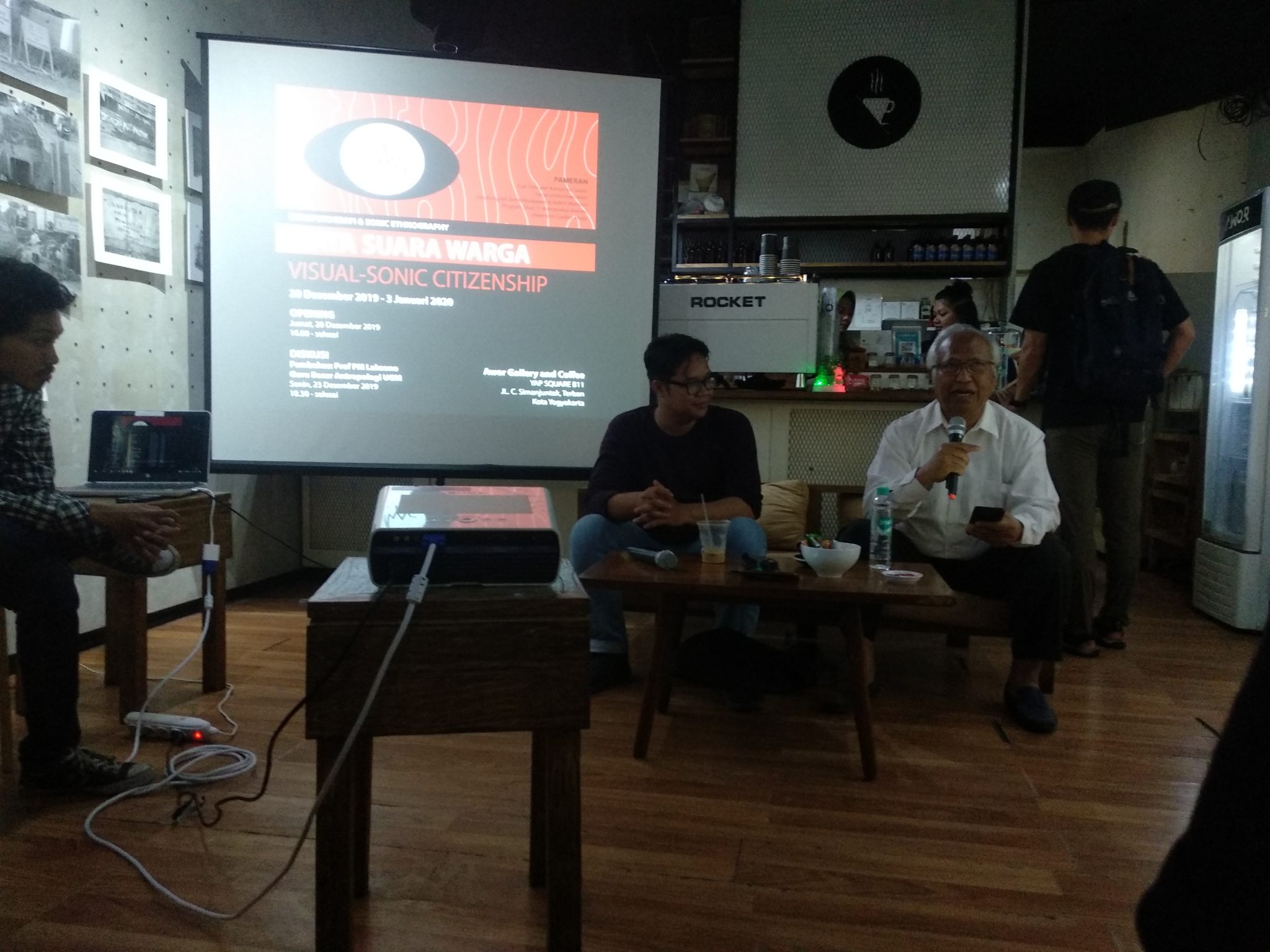

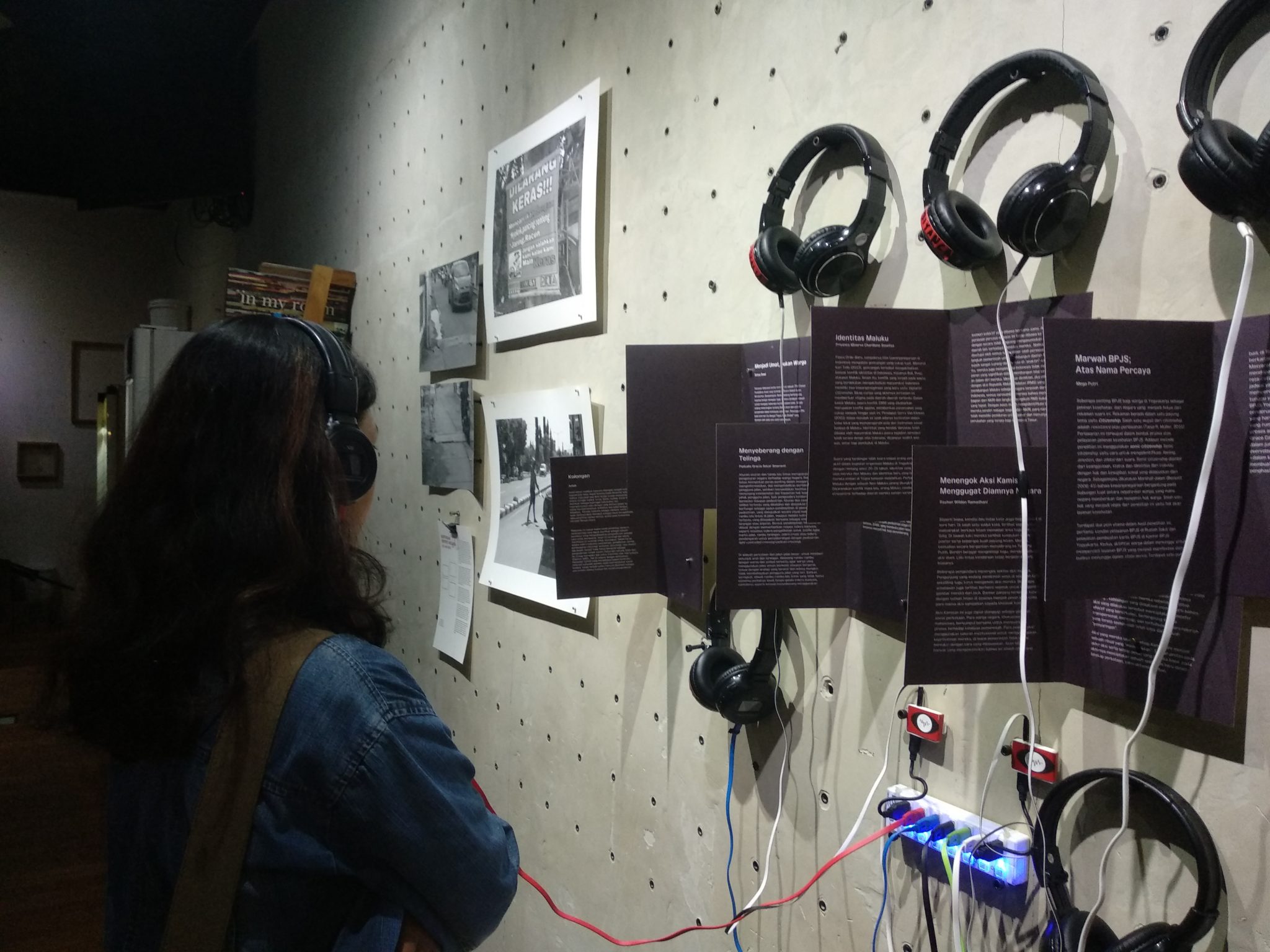

The room was square, only about 7×12 feet. Left and right to the entry, black and white photographs hung tightly on the wall thanks to some magnet, along with ten black headphones ready to be used. Some visitors were closely looking at the pictures and accompanying texts before them, while the others were using the headphones to listen to some audio files. Several wooden chairs were placed side to side, making a rectangle in the center of the room. A long table was set opposite of the chairs, next to the cashier, coffee machines, and the menu list.

Described was the first night of Mata Suara Warga exhibition in Awor Gallery and Coffee on 20 December 2019. The arrangement lasted two weeks, showcasing photo essays and sound compositions surrounding the theme of Citizenship. The pieces were produced by students of the Ethnophotography course and Culture and Human Senses course organized by the Department of Cultural Anthropology Universitas Gadjah Mada.

Unfortunately, when we visited, the layout of the room has returned to its original state as a café. The current layout made it difficult for the visitors to roam and look around; one of us even tripped on a customer’s laptop charger. The exhibition layout was only restored on the fourth day of the exhibition to accommodate discussion attended by Prof. Dr. Paschalis Maria Laksono, an Honorary Professor at the Department of Cultural Anthropology Universitas Gadjah Mada.

©Rasya/Bal

In the discussion, Laksono remarked that he didn’t see any citizenship being showcased. “Instead of showing citizenship, the exhibition is showing the absence of it,” he said. He reckoned that, in building a narrative, an exhibition needed two functions: identification and prediction. Ironically, after identifying the correlations between subjects in one piece and amongst the pieces, he found the predicate to be “absent”; citizenship, in the exhibition, was absent.

For instance, Laksono mentioned the piece titled “Mass Action”, which was divided into three photographs: Yogyakarta Monument, crowd, and a banner saying “increase labor wage”. He explained that the predictive function in the piece was “a crowd demanding labor wage increase in Yogyakarta”. The title “Mass Action”, Laksono added, did not represent any citizenship, as mass did not equal citizenship. “Citizens are not included in the narrative, only mass,” he observed.

Hence, Laksono sensed that the citizenship narrative was absent. He also claimed that there was still room to combine visuals and sonic in the form of sound compositions. “Speaking in terms of filmography, the exhibition is a piece of footage. It’s yet to be the whole film,” he added. That, he noted, was due to the separation of photographs and compositions. “There’s a thesis that has to be proclaimed before executing the exhibition. It is not only a matter of showcasing recordings in the exhibition venues,” he resounded.

Then, what is citizenship? When interviewed after the discussion, Muhammad Zamzam Fauzanafi elaborated, “Simply defined, citizenship is the relationship between citizens and the state.” The relation might be formal or informal. Zamzam, the lecturer who led the class project, clarified that the citizenship brought about in the exhibition was an informal one. It came to life in practical forms, such as protests against the state and state indoctrinations through means of regulations.

The exhibition showcased photographs in a number of narratives, for instance, the series titled “Space Arrangements”. The photograph captured an enclosed area under the flyover near Lempuyangan Station. According to Pipin Mukharomah, the student who took the photograph, the site used to be occupied by street merchants. Through an interview with locals, Pipin discovered that the President once visited the area and decided to alter its function into a parking space. The area became confined after an argument between the merchants and law enforcement personnel. “The lot was once a public space allowed to be occupied by anyone, but the current arrangements eliminated such freedom,” Pipin affirmed. The organizer hung Pipin’s pieces alongside other depictions of space arrangements in Malioboro.

©Rasya/Bal

Besides photographs, sound compositions were also displayed. One of them, titled “Visiting the Act of Kamisan, Challenging the State’s Silence”, told the story of the Kamisan act of silence which, surprisingly, turned out to generate boisterous sounds. Rayhan Wildan, the student who recorded the sounds, explained how he tried to record the act through the perspective of the mass. The composition recorded how the mob gathered, stayed in silence, held post-event discussions, sang the song “Darah Juang” (which translates to “The Blood of Struggles”), and wrapped up the event with jargons of the fight for human rights. “The act was a realization of citizenship, the act of voicing people’s aspirations to the government,” he pointed out.

Rayhan mentioned that, during the process, he immersed himself in the mass action for approximately two months. Throughout the months, he successfully produced photographs, sound compositions, and writings. Later, he submitted four photographs and their respective captions for the exhibition. One of the photographs passed the curation process and was exhibited along with other pictures from the event Gejayan Memanggil under the title of “Mass Action”.

©Rasya/Bal

Speaking about the photographs’ curation process, Zamzam admitted that his students’ submissions varied widely. Initially, he meant for every student’s photograph to exhibited. However, as he tried to balance the narratives, Zamzam and Nia—a cultural anthropology student who graduated from ISI Yogyakarta photography studies—eventually only picked the best ones. They collected photos with similar themes and gathered them to create a greater narrative. In comparison, he considered curating sound compositions easier, as the submissions already fit predetermined requirements. He merely needed to edit certain accompanying texts.

Zamzam noted that visuals and sonics in the forms of photographs and sound compositions were parts of sensory ethnography. In sensory ethnography, anthropology came closer to being pieces of art. “Nowadays, it is only common for ethnography to end up in exhibitions as the final results turned out to be art pieces,” he affirmed. Compared to pure art, the only difference lied on how photos and compositions attempted to achieve the objective of ethnography, which was to apprehend how humans live in particular surroundings instead of capturing the environment itself.

Zamzam felt that the curative process and the preparation went swiftly. “The preparation for past exhibitions used to take up a whole year, including months of curating pieces,” he recalled. Unlike previous exhibitions, this event was produced as a class project and included as a part of the scoring process. He tried to integrate the event to his class as he realized, nowadays, students only came to study for the sake of grades instead of aiming to take part in collective productive activities.

Later on, Zamzam told stories of how the exhibition once reached Europe after receiving a substantial amount of sponsorship. The first exhibition was established in 1990 and eventually became an annual event. It abruptly ended in 1997, in which the exhibition brought up the theme of elections. Gradually, Zamzam learned that the event left a lot of room for improvements. “Plenty of the details in the exhibition received critiques, particularly from ethnophotography experts who attended. But it’s fine; my only objective was to restart the exhibition which went idle for an extensive period of time,” he wrapped up.

Writer: Rizal Zulfiqri

Editor: Rasya Swarnasta

Translator: Medisita Febrina