©Natasya/Bal

This article was originally published in Indonesian on April 5, 2023

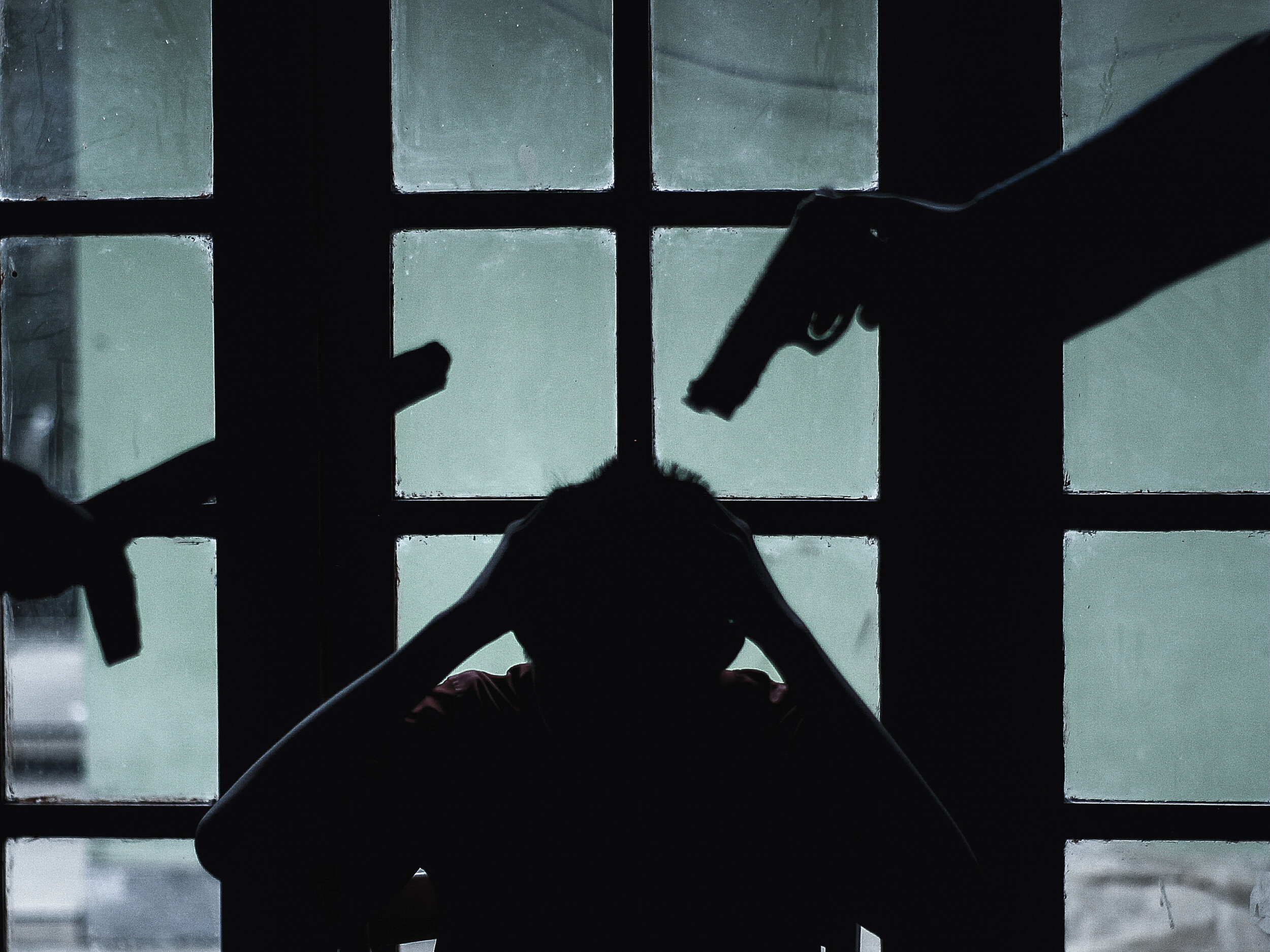

The heat of the barrel. The sharp pounding of the chair legs. The plea, the defense. Wrongful arrests have never been easy to set straight, and so has the wrongful arrest of klitih* in Gedongkuning. The case procedure is protracted–and no clarity has been seen for the victim, the defendants, their parents, or even the justice. The regional police also refused to provide an official statement regarding the latest data of the case because the final verdict has not yet been given. “Which klitih case are you referring to? Which part of Gedongkuning are you referring to? You have to be more specific,” said the Public Relations of Yogyakarta Regional Police (Polda Yogyakarta) to BALAIRUNG, avoiding giving detailed information regarding the Gedongkuning klitih case on Thursday, February 2, 2023.

The defendant’s parents’ sobbing was unbearable as they told of the police’s neglect during persecution. Andayani and Menik, the mothers of Andi and Fandi, defendants of the wrongful arrest of the Klitih Gedongkuning, recounted the law enforcement process by the authorities on Wednesday, December 28, 2022. Investigators always ruled out evidence of irregularities in the investigation process, such as the loss of several CCTV recordings and inconsistent evidence. Ironically, instead of seeing by herself, Menik had to witness the bruises on Fandi’s neck through press conference videos on the internet. “On June 9, Fandi said that he was beaten, even had a gun pointed at him at the detention center,” she explained. According to Andayani, the judges’ sentences spanning 6-10 years for the five victims disregarded the violence inflicted by the police.

Yogyakarta Legal Aid Institute (LBH Yogyakarta) had formerly reported the wrongful arrest case of Klitih Gedongkuning to the National Human Rights Commission (Komnas HAM). According to Julian Dwi Prasetya, Director of LBH Yogyakarta, Komnas HAM has written to the Yogyakarta District Court regarding the violence during the investigation, but nothing has been processed. Julian explained that investigators should not commit acts of violence against detainees or suspected perpetrators. Investigators are responsible for the safety of the people they hold, referring to the Regulation of the Head of the Indonesian National Police No. 15/2006 concerning the Professional Ethics Code of Police Investigators. “However, as a matter of fact, violence was still used by investigators while detaining the suspects,” he said.

Regarding the allegation of police brutality, Verena Sri Wahyuningsih, Public Relations of Polda Yogyakarta, explained that police too could make mistakes while handling cases. “Officers are no saints,” she asserted. Moreover, as Verena unfolded, a misconducted officer is counted as a rogue cop. Thus, it is vital to investigate their background. She also stated rogue cops should receive the punishment.

On the contrary, Herlambang Perdana Wiratraman, lecturer at the Law Faculty of UGM, stated that how the police force handles their officers’ violations is still insufficient. There was a pattern of the police protecting fellow officers by covering up their misconduct and ignoring the public’s outcry regarding the violence. “The police do not uphold integrity properly, far from the ideal concept of building a police force that protects and keeps the community safe,” said Herlambang.

Systemic Violence Has Always Been There

Herlambang declared that the police keep reproducing violence to resolve cases, even frequently upholding the law discriminatively–far from being professional. He stated that violence is not only culturally engraved in the police but also systematically engraved. It is no surprise that violence cases done by officers are everywhere. Herlambang explained, based on data, that the most significant number of complaints received by Komnas HAM regarding human rights violations consistently identifies the police as the main actors involved, and this trend persists from year to year. The explanation is supported by data issued by Komnas HAM that there were 2.580 complaints of police brutality in 2022.

Speaking of police brutality against klitih cases, as a klitih observer, Yahya Kurniawan stated that the pattern of resolving klitih issues was always the same: using violence as the key. He said the klitih suspects were captured and beaten. Besides, according to Yahya, officers are reluctant to deal with street crime cases because they are not profitable, unlike the narcotics cases linked with bribery. Becoming familiar with klitih through in-depth research, Yahya said that there were loads of police violence against klitih and similar patterns of handling it.

Yahya said that officers brutally tortured the suspects during the investigation process. The torture got worse as their wail went on. According to Yahya, officers were unmoved by the defendants’ poor condition. Officers even went so far as pointing a hot barrel at the suspects. “A friend of mine (a klitih member) was caught on the street. He was taken to a hotel to be tortured to induce a false confession,” Yahya told BALAIRUNG.

Reflecting on the increasing number of police violence cases, Herlambang said impunity for police brutality is commonplace. According to him, upholding the law by violence is inhumane–just like what we found in the wrongful arrest of klitih in Gedongkuning. “The police learned no lesson nor evaluation. There is no development found within the institution,” he said.

No Light at the End of the Tunnel

As time passes, much evidence of police brutality remains futile. One of the pieces of evidence is shown in the Final Report on Examination made by the Yogyakarta Representative of the Ombudsman Indonesia. The report showed that physical and administrative violence was used in the Klitih Gedongkuning case. Budi Masturi, Head of Yogyakarta Representative of the Ombudsman Indonesia, stated that the Ombudsman affirmed that both violence were present. According to Masturi, the investigators were proven to have violated the law by arresting the defendants without a warrant, violating the legal procedures for police investigation reports (Berita Acara Pemeriksaan), and committing violence. “Today, February 2, we have reported and proved that maladministration has happened. We have given the regional police (Polda) a recommendation letter to impose a sanction on the investigators.” Matsuri explained.

Furthermore, Matsuri stated that if the recommendation is not followed up within thirty days, the case would be forwarded to the National Ombudsman in Jakarta. He was sure that the advice from the Ombudsman would be impactful for every party involved. “The police were quite committed to the case,” he explained, “Regarding the verdict, it depends on the lawyer and how they capitalize our recommendations.”

When BALAIRUNG asked Polda Yogyakarta regarding the Yogyakarta Representative of the Ombudsman Indonesia’s recommendation letter, Verena said she had no clue. “A clear follow-up would be given if there is any recommendation letter from the Ombudsman,” she explained. According to Verena, the police have made an effort to remain neutral, and rogue cops would undoubtedly be given a punishment.

As of the publication of this article on April 5, 2023, there was no further news regarding the submission of the appeal to the Supreme Court by the legal counsels of the defendants. However, a new fact was found in a press conference held by Orang Tua Bergerak (28-03). The misconducted investigators were undergoing an ethics trial held by the police. Badriah, one of the defendants’ parents, was called as a witness to testify for the case back then. “I was called as a witness. Ironically, only two rogue investigators have been investigated, while actually there were many of them.”

The Police Institution’s Failure to Improve

According to Herlambang’s standpoint, the echoing idea of reformation of the police institution ceased functioning from the beginning. Law enforcement attempts are full of problems. “It was full of stratagems and formality. The principle of justice has been deprived,” he said. Herlambang believed the dysfunctionality of the police institution made the public never trust state institutions since good law enforcement reflects law-abiding citizens.

In addition, Herlambang unraveled that the failure of the police institution’s development was also caused by the discriminatory law enforcement by the police. The police were often scapegoating lower institutions with no intent to improve. He added, “When the work of their staff was unprofessional and harmful to the citizens, no high-ranking law enforcer wants to bow out.”

Herlambang affirmed that the attempts to improve the police institutions could only be carried out with humane, integral, and professional leadership. Inadequate leadership with neither bold purpose nor integrity devises no good lesson to law enforcement. “The tenacity of the police institution to solve the police misconduct case should adhere to the established standards,” he concluded.

Translator’s Note:

*Klitih: a term used to describe students, mostly a part of student gangs, who in pairs (one driver, one executor) attack their targets using a motorcycle, usually at night. The term originates from Javanese word, “ngelitih”, meaning “get some air,” and has evolved to “search for victims.” The practice has proliferated from attacking rival student gangs to the general public. See BALAIRUNG Magazine 58, Hiding Violence in Fair Sight.

Writers: Hadistia Leovita, Ilham Maulana, and Vigo Joshua

Editor: Yeni Yuliati

Photographer: Natasya Mutia Dewi

Translator: Tuffahati Athallah