©Arsip/BAL

This article was originally written and published in Indonesian in 1990. It was later re-published in Balairungpress.com Indonesian version on 22 May 2022.

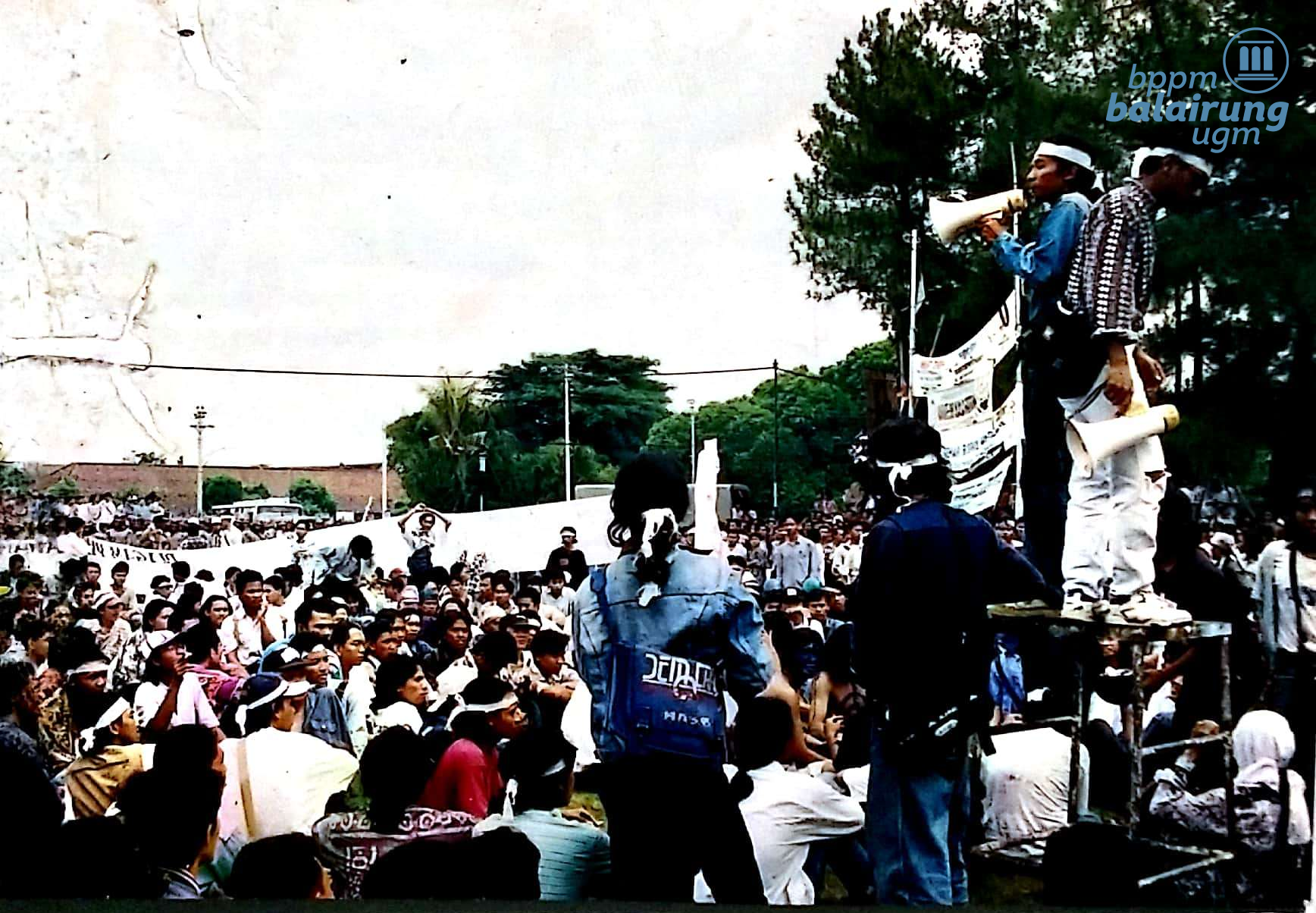

Although the student movement is referred to as a moral movement, historically, this movement spearheaded by students is often intertwined with the political interests of certain elites. During the New Order regime, some observers consider the 1979 and 1978 actions to be the implications of elite political infighting under the President. This is alleged to be a continuity from the successful partnership between students and the military in 1966. Based on this issue, BALAIRUNG re-published an article with the original title “Mahasiswa dan Politik” published in the Special Report rubric of the BALAIRUNG Magazine Issue 12/IV/1990. Below is the article.

In accordance with the partnership strategy implemented in early 1966, the military group provided opportunities for various student action units to act as the spearhead of the New Order. With this radicalism, the emergence of the New Order became easier.

This sense of partnership term is rather vague. For the military, the word means achieving their goals thanks to fellowships with students, which they can utilize when necessary. In contrast, it is a unification for the activists of the ’66 era. Even if the relationship is not necessarily balanced, they dared to criticize and take radical actions against the Old Order regime. It was this partnership with the military that led to the success of the student movement in 1966. Therefore, it is unsurprising that some thought the actions around 1966 were part of the military’s grand design in national political fabrications and often ridiculed by the next generation.

“At that time, we did not feel that the army was using us, nor them by the civilians,” said Cosmas Batubara when asked about the relationship between the military and students when the 1966 action broke out. Cosmas stated that the country’s condition after the September 30th Movement incident was unfortunate. All parties demanded justice, while Sukarno took no action.

“In order to demand justice, we all agreed to join forces. There were artists, students, scholars, and the armed forces. We had almost no limits. Only each of our positions could limit us. But we had the same idea about this movement. There needs to be the New Order,” explained Cosmas Batubara.

Sarwono Kusumaatmaja highlighted the same thing. “It just so happens that we had the same conclusion, we can survive if we are guided by the 1945 Constitution,” he said. For Sarwono, it is the law of nature that the weak are controlled by the strong. Thus, does this mean that the student movement was controlled by a specific party? “I am not saying the Indonesian Armed Forces (ABRI) controlled students. The law of nature says so; the weak are controlled by the strong. Well, who is strong? It is dynamic, not merely black-and-white,” said Sarwono.

According to Cosmas, the issue of political piggybacking that is always attached to every mass movement is not worth arguing about because it is already an objective law. The event of 1966 was an example of a movement that took advantage of each other among the sides involved.

Sarwono stated that mass movements aimed at overthrowing forces are different from social movements that only need a conscience and must be able to show no personal or group interest. In Sarwono’s view, mass movements must have a formidable partner so they are not vulnerable to being politicized. “If the one who politicized is strong, we can win. But if they are not, then we become the victims,” said Sarwono.

©Arsip/BAL

Cosmas noticed the emergence of the term political piggybacking was caused by a system that did not work to channel the aspirations of existing groups. Since before the Proclamation, students have always played a role as a mobilizer against the stagnant political system. “In any way, the student movement will definitely come out if there is political stagnation,” he said.

Does this mean that there was political stagnation between 1974 and 1978 because, at that time, there were student actions? Cosmas further stated that a political overhaul is urgently needed in a stagnant political system. This overhaul was carried out in a targeted and planned manner toward making a well-functioning political system. This is called political development. This political development was carried out by the ’66 movement and continued consequently by Soeharto as president.

However, it turned out that the younger generation saw the course of development not as it should be. Thus, actions in 1974 and 1978 arose. Cosmas stated that the younger generation at that time lacked patience and saw that development was slow. “In fact, the development requires a long process,” he explained.

Therefore, Cosmas disagreed with the actions of 1974 or 1978. “I myself have said to Hariman Siregar (Chairman of Universitas Indonesia (UI) Student Council 1974) during a discussion at UI. After 1966, we should not do any more mass activities. I said this is not right,” said Cosmas. “I did not agree with demonstrations, even though I was a demonstrator (during the 1966 movement),” he added.

Sarwono saw the actions of 1974 and 1978 as movements that lacked a definite and complete concept. So did the actions of 1966 itself. “If you say that the actions in 1966 had a concept, namely Tritura (the three demands of students towards the government). That is called mythicizing, abstraction,” he said. “Tritura is the motto of the struggle to unite all existing potentials,” Sarwono added.

With actions, the problems revealed will become more tangible and specific. The 1966 actions, according to Sarwono, generally discussed whether Indonesia became an Islamic, federal, or Pancasila state. The actions of 1988 and 1989 questioned the impacts of development, such as Kedungombo and Kacapiring.¹ Regarding the 1990 student actions, Cosmas sees that it did not need to happen because the important thing is how to encourage the political system to function more to answer society’s problems. “This can not be done with demonstrations.”

“We must do something. The generation of ’66 spirit must be our inspiration,” said Hatta Albanik, Chairman of the Student Council of Universitas Padjadjaran and Hariman Siregar, on New Year’s Eve 1974. High-ranking officials and Chinese people are considered to be in charge of the situation. Calls were made to rickshaw drivers and the unemployed. Meanwhile, workers in Tanjung Priok, through a representative, expressed their support for students.

On 9 January 1974, students staged a demonstration against Soeharto’s group of military advisers, known as Aspri (Asisten Pribadi), and Japan. Dolls depicting Sudjono Humardhani and Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka in Bandung and Jakarta were burned. Students continued the movement and even multiplied it. On 14 January 1974, students demonstrated at Halim Perdanakusuma airport in protest against Tanaka’s arrival. Contact between demonstrators and guests from Japan did not take place. Therefore, frustration and temperature arose. On 15 January 1974, the catastrophe of January 15 (later known as the Malari Incident) broke out.The question following the Malari Incident was why student protests targeted Aspri and why Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka triggered the treason outbreak that claimed nine lives, damaged the Pasar Senin building, and destroyed several vehicles after that Malari Incident?

H.C. Princen and Fauzi Ridjal: There Must be Infiltration

©Arsip/BAL

Many observers said that the 1974 riot could not be separated from the elite-level political competition that occurred fiercely at that time. The political interpretation stated that since 1972, there began to be a conflict of influence around the President. Two groups were vying for the President’s attention and imposing their economic strategies, not least their political dominance.

On the one hand, General Ali Murtopo and Aspri chose Japan’s economic development strategy. On the other hand, a group supported by General Sumitro chose the US economic development strategy. This rivalry between the two generals is often referred to by observers as the current that led to the outbreak of Malari Incident.

“General Sumitro’s men always asked me about my relationship with General Ali Murtopo,” said H.C. Princen when asked about the Malari Incident’s relationship with the two generals. The human rights defender accused of being the driving force behind the 15th January 1974 riot claimed to be well acquainted with Ali Murtopo. “But that does not mean we shared the same political aspiration,” he added.

So what about the elements of political backing on student movements, as alleged by General Ali Murtopo shortly after the incident? In the book, Fakta, Analisa Lengkap dan Latar Belakang Peristiwa 15 Januari 1974 written by a close associate of Ali Murtopo, it is stated that the pure demonstration of the students had been distorted from its original purpose.

“The student movement could be an iceberg, a giant chunk of ice,” Princen said. “Usually, the chunk below the surface is bigger than the above,” he added. According to Princen, there is usually a ‘game’ at play in this invisible bottom. “This part is uncontrollable and allows for political piggybacking,” Princen explained.

For Princen, the student movement was never independent. The Generation of ’66 clearly was quite linked to the military. “The ’74 movement definitely had been infiltrated. There were students used, but not all of them,” he said. Princen even considered the ’78 movement as a creation of the military. “Yes, at that time, there was an attempt by part of the military to thwart the 1978 MPR (the People Consultative’s Assembly) General Court,” he said without wanting to elaborate.

Meanwhile, according to Fauzi Ridjal, the student movement in the 1970s showed independence because there was an estrangement between campus life and political dynamics outside the campus. The campus became free of interference from extra-campus organizations or political parties.

This student activist of the 1970s pointed out that the election of Hariman Siregar as Chairman of the Student Council of Universitas Indonesia sparked campus freedom from outside forces. “Hariman Siregar is the first person since the New Order who does not represent a large extra-campus organization,” explained Fauzi, the Chairman of the Hatta Library Foundation. “He is not part of the HMI (Muslim Student’s Association),” added Fauzi, who was once active in the Yogyakarta Socialist Student Movement.

When asked about the connection between the actions of the ’74 students and elite-level political conflicts, Fauzi cast doubt on the political interpretation. “Is there really an elite-level political conflict?” asked Fauzi. “How do we measure it? There was no political statement from them. And in formal juridical terms, there is no such conflict, right?”

While regarding the issue of political piggybacking, Fauzi admitted that he preferred the term cooperation. Everyone has the same interests. Short-term interests can occur at any time, depending on the assessment of the arising issues. “So political piggybacking is not strange,” he said.

In line with Princen, Fauzi stated that the student movement could be politically piggybacked. Indeed, in general, people always say that students are often backed by political interests because their potential is weak. They have no political assets and no financial assets. “Therefore, the student movement is very easy to operate with various assistance,” Fauzi said.

By mid-1976, there were widespread news stories that revealed covert scandals among high-ranking officials, corruption, and abuses of power. Students then critically examined these cases. The implementation of the 1977 General Election, which was considered unfair, followed by the emergence of national leadership issues ahead of the 1978 MPR General Court, encouraged student actions in various major cities in Indonesia.

In doing their actions, students form a federation among the Student Council, a legal organization at the university level. The federation made several pledges, such as the October 1, 1977 Pledge (Bogor) and the October 28, 1977 Pledge (Bandung). The Indonesian Student Council meeting in Surabaya on November 10, 1977, finally followed a march to the Taman Makam Pahlawan (heroes’ cemetery).

In various major cities, there were also student demonstrations. In Jakarta, students came out with the equity issue, rejecting unfair economic policies, for example, regarding fuel and the increase in city bus fares. In Yogyakarta, students raised the issue of returning to Pancasila and the 45 State Constitution purely and consequently. In Ujung Pandang (now Makassar), Padang, and Medan, students protested against various cases of abuse and called for the government’s attention to fix them. In Bandung, students rejected the renomination of General Suharto as the next president. That last statement was made in relation to the upcoming 1978 MPR General Court, one of whose agenda was to elect a president.

Indro Cahyono: The Need for a Political Concept

©Arsip/BAL

“The student movement cannot be separated from political momentum,” said Indro Cahyono, a student activist in the late 1970s. “The function of politics is inherent in the student body, so every time there is a political opportunity–a chance of success or failure, for example, a change of president or elite conflicts that mean political momentum–will give birth to a student movement,” said Indro Cahyono.

Therefore, whenever there is a student movement, the influencing force behind the student movement becomes the central issue that arises. On one side, there are elite political conflicts, for example. On the other hand, students in politics lack political infrastructure and facilities. “That is why they tend to be influenced by these elites,” said Indro Cahyono. “Even though students are not in the position to be influenced,” he added.

“In truth, this is only a coincidence or political coefficients,” said the Chairman of Sekretariat Bersama Kelestarian dan Perlindungan Hutan Indonesia (SKEPHI). “Rather, the existing political conflict is used by the students as a positive democratic tool,” he said.

According to Indro, the issue of political piggybacking is merely political gossip. It will always be the case because every social interaction is not a linear line. Interactions never go one way. “It is in such networks that the term political piggybacking grows,” he stressed. Students do not need to be deceived by the issue of political piggybacking because it can discourage the meaning of students’ movement to the point of destroying the students’ movement itself.

At least, that is what could be learned from the experience of the student movement that emerged in 1977–1978. At that time, students were so consumed by issues that the student movement must be pure, having no political influence nor cooperation with other parties. Students are also consumed by government issues, which say the government will pay attention if the student movement is pure.

“We have no political affiliation with political forces in society, but it is ironic that the student movement is still muzzled,” said Indro. “Even the army occupied the campus, and the Student Council was disbanded,” added the Presidium Member of the Acting Chairman of the ITB Student Council 1977-1978.

The 1978 Student Movement was ironic. Regarding its support and political conception, it far exceeds what was done in 1966 or 1974. This movement has covered several major cities, even reaching Irian. While 1966 and 1974 only took place in Jakarta. The long plea put forward by movement figures on the court showed how they already had a better conception of politics than before.

According to Indro Cahyono, the student movement must have a clear concept and role of what they want to bring. “Because if not, students can be accused of being reactionists. And this is very dangerous even if the organization is legal,” explained Indro Cahyono.

Many say that the student movement is a moral movement, so why should it have to conceptualize everything? According to Indro Cahyono, if this is the case, students will be involved in political struggles in which they are ready with a lot of mass, such as parties and community organizations. “Golkar, PPP, PDI, NU, and Muhammadiyah are political giants. Do students want to fight these elephants?” asked Indro Cahyono.

At a minimum, students must conceptualize their politics if they want to move. Indro Cahyono then pointed to examples of student movements in China, Cuba, England, and the Netherlands that had mature concepts so that the movements were not reactionary. “Even in many ways, the student movement can be the embryo of a political party,” he said. Benazir Bhutto, for example, when she studied in the US, conceived a certain political conception. She gained the support of certain political groups so that her movement could eventually become a major party.

“If the student movement is to succeed, it should not be based only on campus. Look for activities outside, join lots of communities,” suggested Indro Cahyono. Because if they already have a base in the community, students will be well protected when wanted by the army. “Unlike how it has always been, playing cat-and-mouse with the army on campus,” he concluded.

Footnote

- The Kedungombo case was an incident of residents refusing to evict and relocate when their land was to be used as the Kedungombo Reservoir. The residents’ refusal was due to the small amount of compensation given. Meanwhile, the Kacapiring case was about a land dispute between the Government of Bandung and the people around the Kacapiring area in 1989.

This article is rewritten and edited by Han Revanda Putra, Marshanda Farah Noviana, and Naufal Ridhwan Aly. Translated by Putri Kusuma Dewi.