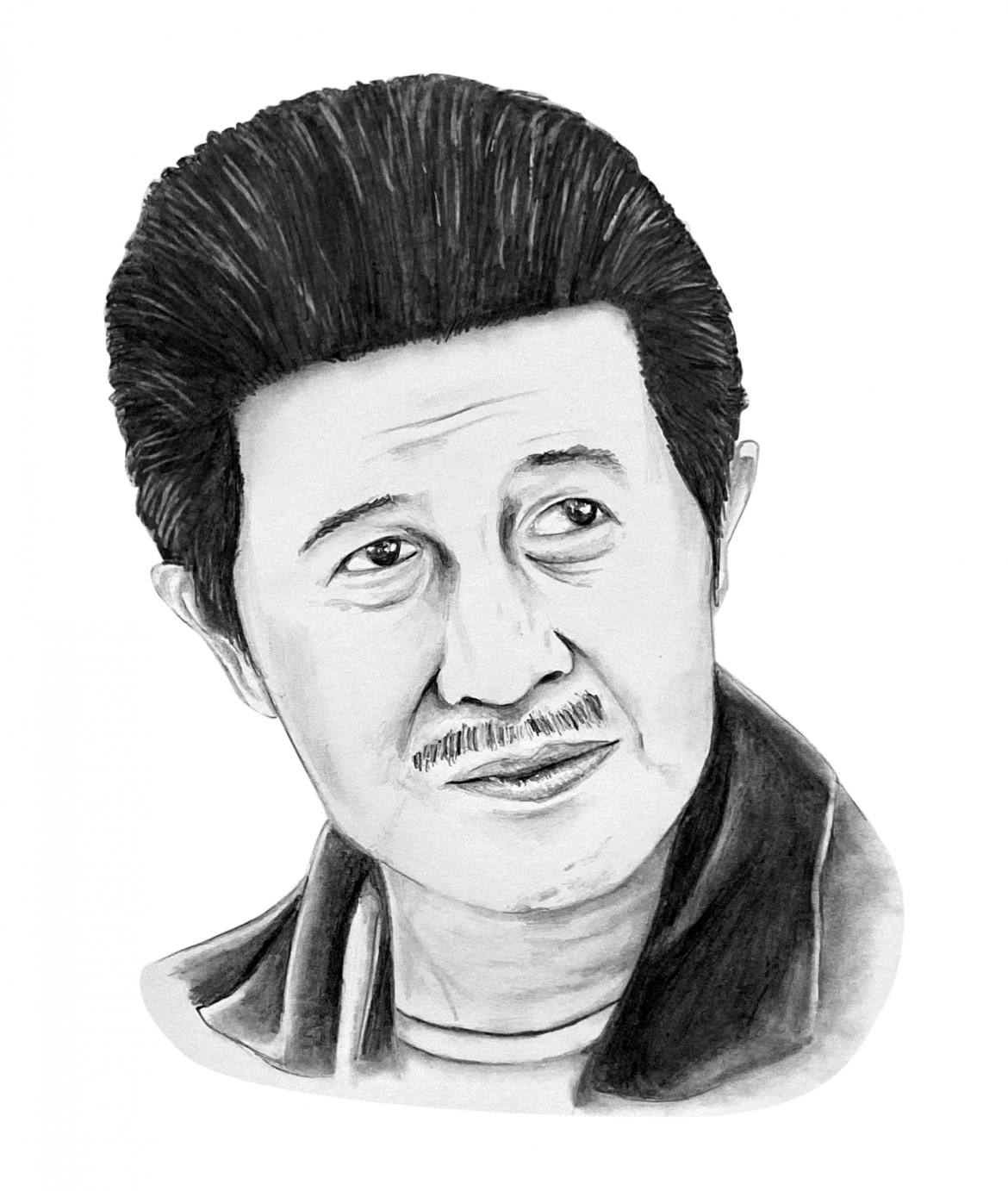

©Haifa/BAL

Indonesian literary award, Kusala Sastra Khatulistiwa, honored the anthology of short stories, Tea and The Betrayer (Teh dan Pengkhianat) as the best literary works in the category of prose in 2019. That was the second award for Iksaka Banu, after his anthology of short stories, Everything for Hindia (Semua untuk Hindia), won Kusala Sastra Khatulistiwa in 2014. His two literary works have a topic of Indonesian history, Iksaka Banu’s unique theme, which appears in his short stories and novel.

From any time setting on the Indonesian historical periods, colonialism has dominated Iksaka Banu’s two anthologies of short stories. Iksaka Banu presents a new narration on Indonesian historical fiction by becoming the Netherlands as the central character. He tries to explain a counter-perspective through his humanistic protagonist. Balairung had an opportunity to do an interview with Iksaka Banu for quarrying his perspectives.

Your delineation of past events is very realistic. Is your gathered-source is a primary source, which means you did literature study, archives, and others?

I think it depends on the coverage of the ongoing story, also depends on if there any funding sources. When writing the novel Sang Raja, unfortunately, I got research funding from the sponsor. So, for a week I went to Kudus, met with Nitisemito’s legacy, visiting his house of twin at Kali Gellis, seeing Kretek Museum, and also visiting some prioritized places that I have listed. I also collected the data from any book and article on an old Netherland newspaper. It also happened when I wrote Pangeran dari Timur. Kurnia Effendi and I had to go to the Netherlands for seeing the places that had been visited by Raden Saleh, the studio he studied painting, his boarding house in Prinsengracht, Mauritius, and others.

Moreover, for the short stories in Semua untuk Hindia and Teh dan Pengkhianat, almost every data I collected from books, Netherland newspapers, and online articles, because there is not much detail that must be delineated.

Are there your works that the idea comes from literary works?

Secondary sources from literary works had little impact as a resource in my works. Except for the short story “Penunjuk Jalan” about Untung Surapati’s childhood within Suzanna, the child of Edeleer Moor, I studied from Surapati written by Abdul Muis and Nicolina Maria Sloot. But there is very little data I collected from that because, on the historical notes written by Leonard Blusse, Untung Surapati since in his childhood lived with Pieter Cnoll family. So, there is a possibility Abdul Muis only retold the work of Nicolina that was the source is fiction.

Although it is a work that tries to balancing fiction and history, historical weighted value has a considerable portion. Do you try to make literary as like one of the sources for studying history?

On the specific line, literary works can be a historical source. Within a note, it only works for contemporary literary works, that recorded social condition, geography, and environmental psychography and the year of the stories were told. For example, when I write a realism novel that recorded youth social life in Jakarta this year (2020), perhaps considered or not, I also recorded the atmosphere of Jakarta in 2020 accurately. It can be a hotel, street, fun park name, even the brand of mobile phone. In the future, it can be used by a writer who lives in 2040, when he/she will write historical fiction about Jakarta in 2020.

A concrete example for this case is Ali Topan Anak, a novel by Teguh Esha. That novel records youth life in the ’70s, from hairstyle, the places they have fun, the brand of motorcycle, the shirt they wore, and others. However, when today we write a story with a background of 1945, and the writer will reuse that story in 2040 as the historical source of the events on 1945, it cannot be responsible for the accuracy of historical notes.

Nevertheless, in your opinion, could a literary work have a position as historical literature? Or do you have a desire to make such a thing becomes?

I do not ever hope the historical fiction I have written becomes historical literature. As you may see, in my book covers, I always write a disclaimer, “A Novel”. In the preface, I used to note that the story inside is just historical fiction, not a historical book.

Literature could loan the historical facts as the story background. On the other hand, it also helps “living” historical actors. In the sense of literature, we may “see” how Diponegoro spoke, how Jan Pieterszoon Coen’s body gestures expressed when he walked, and others. One thing that is impossible to do with the historical note.

Nonetheless, history has to be separated from literature. It could not be used to critic the literary work vice versa. For example, when someone writes a novel titled Candi Borobudur Ciptaan Nabi Sulaiman (Salomon created Borobudur Temple), a historian does not have any legitimacy to judge it, because in the book cover has been written disclaimer, “A Novel”. It must be quite different if the writer claims that it is a historical book. The author must be ready to be called to take a responsible scientific of his argument in front of the official institution.

About my historical fiction books, my primary purpose is just to make the readers, especially the youth, have much interest in understanding our colorful history. There is a lot of things we could learn from history. However, our historical literature presented in a rigid form. The students generally are asked to memorizing the dates of the events and emotionally untied names with their context of life. By applying historical fragments into a short story or novel, perhaps will make them interested in reading history. If they interested in a story in my books, it will attract them to find out historical facts from my historical fiction more representatively.

Why is colonialism period chosen in your short stories, such stories in Semua untuk Hindia and Teh dan Pengkhianat?

The colonialism period attracts me because if we take attention to it, today there is a tendency in our society to forgetting or unrecognized that period as a part of Indonesian history. Perhaps it is because colonialism period writers are the Netherlands, so there is a collective argument, that is not Indonesian history. Furthermore, nowadays, there is an anti-foreign sentiment.

Moreover, for an age, the colonial period was fulfilled with bitterness and anguish our descents had. Life and death were in control by the colonials. The bitterness is inherited through generations, so that causes an unhealed trauma. Unfortunately, instead of finding out a healer, many of us precisely choose to jump away or forgetting that period. Moreover, if it was talked about, it will be going to be judged in binary. The Netherlands will always be seen as the cruels, but Indonesian is still on the right side.

The consequence is that trauma does not disappear until today. Moreover, it is deliberately used for political matters. I want to urge the readers to look back through that period as an integral part of Indonesian history that we must learn from, admit to, and face. Because our existence today, of course, is an outcome of the events our descents have done in their past life, and it happens simultaneously. By learning the worst matter that had done in the past, we should avoid past mistakes for the future.

In Semua untuk Hindia, the opening story is “Selamat Tinggal Hindia” about the end of the Netherlands colonial period, in the time of early Indonesian independence, and the Netherlands were asked to going back to their country. However, “Penabur Benih” is about Netherland ships anchored at Indonesian ports. Semua untuk Hindia frames its short stories with two paralleled stories. What will you say about placing those two stories at the beginning and end of the book? Why do not you do the same thing on Teh dan Pengkhianat?

When Semua untuk Hindia was published, accidentally I had not had another book that is about colonial historical fiction with a kind of that style. So I was worry if, in the beginning, I placed a slow plot such as in “Penabur Benih” perhaps the readers will not keep reading the next stories. So that I deliberately reordered that historical event order to readers could adapt to, make themselves ready to diving over time.

They will begin reading that book from the historical background story that used everyday things and human behavior in today’s context, for example, the car, ship, submachine gun, and others. Then more it pulled over to the past, the followed context they read will be older because of many things or places, or unusual words that I must explain the matters. It is such as jabot (18th-century neck jewelry), cravat (19th-century neck jewelry), doublet (a short tight jacket worn by European (Spanish) men in the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries, an elite complex Tijgersgracht, musketeer (a rifle soldier), and others.

In The dan Pengkhianat, I do not use that pattern anymore because afterward, I have more short stories or novels that are about the colonial period. Furthermore, I also see my readers mostly have an understanding of how I speak in my literary works.

In “Kalabaka” (Teh dan Pengkhianat), the main actor that is the Netherlands delineated has a high humanistic sense. He refused the death penalty to the natives, in the end, he got the death penalty because of his resistance to his military division. Is that thing done to calming the Indonesian sentiment through the Netherlands down with giving them an antagonist image? Then perhaps there is the Netherlands that did not want such a thing to happen?

It is right. Like I said before, in all of my literary works, I want to urge the readers to reimagine the colonial period and its historical actors critically, with the humanistic point of view, not take it in general. We have to remember, once, that even the worst colonial period, from the historiography, could not be disappeared, or jumped away. The past, present, and future of a nation and its people run simultaneously, have a mutual relation.

I also said in some discussions, that if we assumed the Netherlands is cruel, we must be ready to get such an assumption by East Timor that we all Indonesian are cruel taking away their freedom. Although many Indonesian with an open-hearted become a teacher (with an unproperly salary), or a tire repairman, mechanic, or merchant, in East Timor in time of becoming a part of the Indonesian Republic, without bothering the natives. It is like the marginal Netherlands in the past. We can say for example the blacksmith, the ostler, fish trader, merchant, and teacher, that were also not having any problem with the Hindian Bumiputera in the colonial period. So those marginal Netherlands mostly appear in my short stories.

Tanzil writes, “If the writers give more portion to the native characters, we will get more whole images and equal narration about East Indies from the perspectives of the native and Netherlands.” In your works, Indonesian do not become central characters in the stories, so they do not have their various like the Netherlands have. Why are both perspectives not depicted in your works?

I want a little novelty in the point of view. Film, short stories, or novel that have a colonial background, of course, appears before my short stories and books. If you read carefully, almost every colonial film, comic, and novel take up Indonesian perspectives, and automatically the portion for Indonesian character appeared more, for example, “Pasukan Berani Mati”, “Jaka Sembung”, “Si Pitung” film, Surapati novel and others. The Netherlands is delineated as cruel. That is their right to, of course. I do not see there is a problem with the film or novels before my works. Those are very welcome. I want to temporarily change the play, and also the portion of the characters. So, we can see together what was happened.

In your short stories, there are pinned stereotypes given by the Netherlands to the Indonesian. In “Di Atas Kereta Angin”, Si Dullah, Netherland East Indies people, is considered as not proper to riding a bicycle. In “Teh dan Pengkhianat”, Sentot is suspected to be going to defect to the Chinese army and resist the Netherlands, because in the past he joined Batavia’s army during Java War.

Nevertheless, in the end, the stereotype is broken. With a bicycle, Si Dullah could help the “I”. Sentot also is not a betrayer until the end of the story. Do you, except having the opposite will, take down the Netherlands stereotypes as the invader to Indonesian that is the subject?

I did not drive away mainly the historical events virtually, although, as a fiction writer, actually I have the right and creative license to do it. Quentin Tarantino, in “Inglourious Basterds” film without any doubt delineates Hitler not suicide in the bunker such as what history tells us. In his movie, Brad Pitt kills Hitler.

In the name of creative license, I also change the historical plot, but I am rather not doing that. In my short story, Jan Pieterszoon Coen still appears cruel accurately like what is in our and many Netherlands today history. So does “Semua untuk Hindia”, the massacre in Puri Bali still exists. Nothing is changed. The invader is the till invader. Both sides, Netherlands and Indonesian, according to history, admit the existence of that invasion. I only put the fictional characters to be a narrator while offering opposite opinions through some topics.

Is there the good Netherlands? Yes, for sure. In the intellectuals circle, we know some names such as Cornelis Chastelein who liberated all of his slaves. We know Multatuli, the author of Max Havelaar, Van Deventer, Pieter Brooshoft, P. A. Daum, and other humanistic figures. It has not included ordinary people. However, there is also cruel, opportunist, bootlicker, rapist bumiputra (the natives).

After the historical novel Raden Saleh written in tandem with Kurnia Effendi published, Are there your works that are in progress? Will your next works have a colonial history background?

Yes, I have one novel about slavery in Batavia that is in progress. Accidentally it is still about colonialism.

Penulis: Rasya Swarnasta

Penyunting: Harits Naufal Arrazie

Ilustrator: Haifa Sausan